Should I write a book? Should you?

A candid interview with author Jeremy Gordon about what writing a novel did to and for him.

Should I write a book?

This is a question that has been in the back of my mind since childhood, back when I considered it not a matter of “if” so much as “when.” When I began working in media, the question faded as I busied myself with other kinds of writing. I was presented the opportunity—or something close to it—to pursue a book maybe twice, off the backs of well-received essays that I wrote for various outlets. That’s generally how it goes for lucky writers in this biz: You publish a viral piece that leads discourse for a couple of days, and then some literary agent comes calling, inquiring whether you’d be interested in turning that piece into a nonfiction book. A hybrid piece about, say, the iconography and cultural significance of bubble tea will become a book about Asian American identity and food. A critical essay about, for example, the neoliberal weaponization of identity politics will become a book about how progressive politics lost its way, or something. (This was, of course, pre-whatever the fuck is happening to DEI right now—different times, man.) Sometimes these concepts bear out for 200 pages or however long is acceptable for a book. Often they don’t, and that’s how you end up with a weak work straining beyond its weight—plumped up and produced too quickly in the hopes of capitalizing on the moment, like a hen that has been force-fed so it can end up on the rotisserie spits at Costco—that really should’ve just remained a magazine piece, which is how I feel about most such books.

I let these various opportunities slip by partly because I’m stupid, and partly because I know in my heart that the kind of book I would like to write—that would have my soul and my pride and my pleasure—is a novel1. Please feel free to roll your eyes now. A newsperson who wishes to abscond to the world of make-believe, how predictable. And not just that, but one with literary ambitions—kill me!

I know what my novel will be; I have for the past three years or so. The desire to turn it into a reality comes and goes, but it’s always there, breathing.

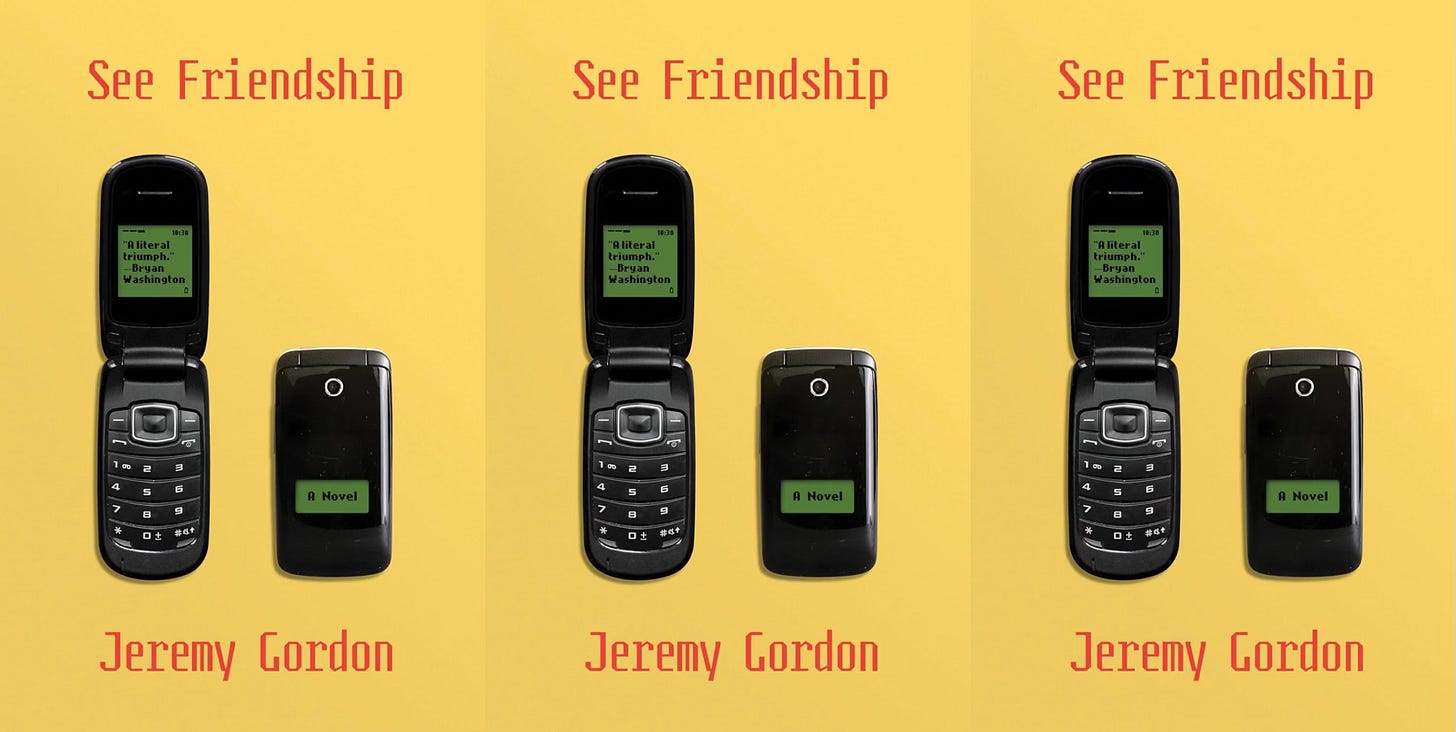

What would it be like to actually write a book, though? In this world—in this economy? To answer this self-serving question, I turned to Jeremy Gordon, a writer and editor and online-media veteran whose work I like. About a month after Jeremy published his debut novel, See Friendship (available here)—which I did read, thank you very much—we had this phone conversation about writing and releasing a novel, good ideas versus bad ideas, transformation, and more. Maybe it’ll be as interesting/clarifying/helpful for you as it was for me:

JENNY: As you know, the main line of inquiry today is, broadly, “Should I write a book?” To that end: Why did you write your book?

JEREMY: I had always aspired to write a novel, going back to high school or grade school, even. The one thing I wasn’t sure about was the form that it would take. When I moved into journalism full-time, I was focused on making a living through that, which is broadly always the theme of my writing life and professional experience: How do I make a little bit of money doing this? Not to be totally financially oriented, but it was a very real concern. I came out of college at a moment when digital media was at its peak: Companies were hiring very diversely and broadly, the classic model of the magazine was collapsing, and newspapers were in this transitional mode. It felt like there were these opportunities for young millennials who were psychically ready to work for very little money. It’s easy to take for granted, now that we’re staring at the edge of another recession, but people did not have jobs in 2010. I remember graduating into an environment where it was hard to get work in your chosen field, and all of these jobs suddenly sprouted up. Even if they would pay $27,000 a year, you would get to live in New York. Setting aside the fact that it’s incredibly difficult to live off $27,000 in New York if you don’t have some sort of financial safety net, it was very tempting.

So I always wanted to write a book in some sense, but I kept finding it delayed by work. I had this—in retrospective, incorrect—belief that there would be this magical moment: If I read X number of novels and Y number of short stories, one day inspiration would strike me, and I would produce a literary work of staggering genius. What I realized, almost like a flash of an epiphany somewhere in my mid-20s, is that you just had to work. I needed to cultivate the same relationship to fiction that I had to nonfiction, which is: setting aside the time and sitting down and just doing it, working for long periods with little to no reward. With nonfiction, I was at least used to the dopamine rush of working on a piece—edits—it goes up. The longest I had worked on a piece in my 20s, early on in my career, was maybe four months. But with fiction, you’re just laboring for the longest time with no obvious payoff, so to speak. Once I embraced that mindset of just sitting down and working on it, it began to fall into place. It took a very long time to fall into place, but my initial stabs at what eventually became See Friendship sprouted from that mental pivot of getting down to it.

In terms of actual artistic or intellectual motivation for writing the book, aside from the obvious fact of my being a longtime fan of books, I was drawn to the idea of controlling an entire piece of text by myself with no relationship to the news cycle or matters of relevancy or having any sort of deadline. It was very appealing to just be able to decide something entirely for myself. When you write an article, it gets put through the wringer in terms of edits to get the tone or serve the needs of the publication. A novel was an enormously appealing vehicle to see what I had on my own.

From conception to completion, how long did writing your book take you?

The very first version of the book was a short story that I wrote just for myself in the summer of 2019. Not long after, I was sharing it with my wife Jen, who’s also a writer, and she said, “I really enjoyed this, but I felt like I wanted more. I feel like this could become a novel.” The short story was not something that I was going to try to get published; it was really just a proof of concept of thoughts that I had going on. But I used the short story as an outline for what became the novel. It took me a year and a half to complete a first draft, and I was revising it for another year before my agent and I tried to sell it, and then it took a little bit longer to sell. It was delayed a couple times by the political environment—basically, there were two moments when the book was on submission and we decided to artificially delay sending it out because it was going to potentially intersect with the midterm elections. Obviously, there are a lot of people who work in publishing who lean more liberal in their politics, and if the result was especially bad for Democrats, as was being predicted at the time, there were concerns that those people wouldn’t be in the headspace to sit with it. But when it did sell, I was told—and this is borne out by what happened—that, as a debut novelist, you do not want to be within six months of the election, good or bad, just because all the oxygen was going to be sucked out by political books.

You’re really trying to hit someone at the exact moment they might be ready for your book. You can only send the book to someone once, and you can’t just ask, “Are you in a space to receive this novel right now?” There are so many factors that go into someone’s emotional preparedness to read a novel, you’d run out of space thinking about all the different variables, so it’s really just trying to get lucky. In a different world, See Friendship probably would’ve come out maybe a year, a year and a half ago. But yeah, shit happens.

Aside from your own desire to write a novel going all the way back to childhood, did you have any external motivations? Take your protagonist: He is a long-time staff writer who gets this idea of doing a podcast, in part, because it’s sort of the next level in his career. This is also kind of like how books work in media, even if people don’t say so explicitly: Getting a book deal is almost proof that you’re moving on up or otherwise advancing your career. Did that ambient expectation factor at all into your deciding seriously to pursue this?

My thinking was more motivated by the writing of it as a challenge or experiment to myself. I never really considered whether it was the next step in my career to suddenly produce a book, but I was certainly aware of the fact that I didn’t just want to keep doing the same thing over and over again, regardless of what that was. There’s always been a part of me that’s looking ahead to the next thing. There was a long stretch where I was writing criticism, which I really enjoyed, but then I got a little tired of just sitting with my own thoughts all day. Then I had an opportunity to pursue more interviews or features or more standard journalistic pieces where I was calling people around and piecing together information, and that was very valuable. If you look at the progression of the pieces that I’ve written over my career, they began on the shorter side and then worked their way up: I went from writing an 800-word review to a 2,000-word review to a 4,000-word essay to an 8,000-word feature. On a very brute force, logistical level, I was like, can I write a piece of text that is 60,000–80,000 words or longer? Can I sustain it and make it make sense and hang together?

But I would be lying if I said the career thing didn’t come in the back of my head. Not in any sort of “I hope this does this for me” sense, more: You make choices in your career, and choosing to write a novel as opposed to working on a book proposal for an essay collection or a reported book or whatever—I was aware that choosing to spend my time in this avenue might pull away from the possibility for me to do something else that might seem a little more logical, if you were trying to give me career guidance. But at the same time, I kind of just wanted to do it, and that was the strongest motivating factor. Within that, I considered the possibilities of what if this doesn’t go well, what if it doesn’t sell, what if everyone hates it, and all that stuff—and I just decided, well, let’s see.

What, in your mind, was the worst possible scenario that could happen?

I think it would’ve bummed me out if it absolutely had no reception whatsoever, positive or negative. I can’t lie and say that I would’ve taken a barrage of negative criticism with a smile, but at least it would’ve been informative of some strong pathological rejection of everything that I had going on for me—which would be bracing, but you do what you can. I think total silence in every direction would’ve been very disappointing. It’s impossible to project the reaction to anything, but at the very least, you hope that it clicks with someone on some level. As a professional critic, I understand that if you really hate something, it gets stuck in your head a little bit, whereas the worst possible reaction is someone being like, yeah, it was fine, and moving on and never thinking about it again.

Your book has been reviewed by the New York Times as well as other outlets. You had a proper book launch and events and a real rollout. By those measures, it was a success, especially for a debut novel, right?

Yeah. Everyone who I work with on the publishing side, and my literary agency, seems to be pretty happy with how things are going. One thing I’ve learned about publishing is people don’t really lie to you or sugarcoat it; they’ll just straight up say, “We’re not where we wanted to be.” So none of that has come so far.

I’m extremely humbled in a very basic way every time I see an example of my book existing in a bookstore or an airport somewhere out there. You’re not just competing against other books—you’re competing against everything and everyone for someone else’s attention, the myriad millions of ways they could spend it, so to even be considered for someone’s free time is enormously rewarding.

You have a full-time job and you’ve done freelancing. How did you actually find the time to write the book in between all those commitments and having any semblance of a personal life?

When I started writing the book, I was working for the Outline, and in retrospect, it was approaching what ended up being our closure. So I certainly had a lot of free time, when I wasn’t working, to pursue my book. I would start in the morning and often get a lot of writing done, and some days I would be done with work a little early in the afternoon. Honestly, the days kind of just go by; it is really something I worked on every day for a long time. Because I had to do my job while I was writing it, I never ever had the period of time in which I could just take off two weeks or whatever and just spend the whole time luxuriating in the writing. It always was a window that I had to kind of fit it into. Sometimes the window was a little tighter than others, but the benefit was that, over time, it really did pile up. When the Outline got shut down at the start of lockdown, I had written a third of the book at that point. That’s when I decided to focus on this rather than try to get another job, because I had expanded unemployment and severance and my own savings, and I began to freelance a bit. In that period, I finished the book and then continued working on it on the side. This was also the upside of media and freelancing: Knowing how to balance my time and my writing was something that came very second nature to me. The trick for me was to make sure that I wasn’t just rushing to finish it, and that it took the time it needed to take.

Did you feel that intellectual and creative fulfillment—that actual pleasure—every time you sat down to write?

Absolutely. It was enormously satisfying to shape this entire piece of text, guide it by nothing other than my own enjoyment of it. Understanding how to navigate something that long and stitch it together so that it all flowed—that was a brand-new challenge, and I didn’t really understand how to do it until I did it. In hindsight, it was very obvious to me why my previous attempts at writing novels had failed, because I just didn’t believe in the idea and I didn’t care about it enough; inevitably, there would come a moment when my attitude shifted, and I was no longer interested in it. I can sincerely say there was never a moment when I was writing See Friendship that I doubted that I wanted to write it. There were moments when I was unhappy with some of the writing, and there were moments when I thought, oh no, maybe what I’ve written is shitty, but even then, my instinct was to get back at it and make it better and improve it until I was happy. I never, ever considered giving up on it. That was very revealing to me, as someone who is so comfortable giving up on a piece of writing when it’s not interesting to me. To realize the inverse of that—“Oh, this is what it takes to sustain something”—was enormously instructive, especially as I’m considering future book projects and what it takes to pursue that.

I think the book is probably in the same ballpark as some of the writing I’ve done on the internet, but it’s a different mode, and being able to explore that with the liberties of it being fictional, and toying with different voices, was a lot of fun. Even up until the final days I was doing edits, I would be sitting in our living room, cracking up, and Jen would lean over and say, “What are you laughing at?” And my answer would be, literally it’s my own book—I’m laughing at jokes that I wrote in the first draft in 2019 and that have stayed in all the way, and I’m reading it anew, and it’s still making me laugh. And you know what? That’s pretty nice.

How do you know if you actually have a good idea that’s enough to sustain an entire book-length project?

It’s really a personal thing. For me, making the transition from nonfiction into fiction was understanding and accepting that, on some level, I am the writer who I am—which is not to say that everything I write has to be the same, but there are certain things I’m interested in more than other things. I have certain inclinations and personal preferences and a taste profile that is mine, for better and for worse. I wanted to pursue something that made sense for me.

It really came down to being able to think about something and not get sick of it all the time. It’s so easy to get sick of something. I’m working on a second novel, and the germ of it is an idea that I first had in 2019, before I even started See Friendship. I poked at it a little bit, and I put it away because it wasn’t the time, and I picked it up in 2022 and poked at it again, and it wasn’t the time, I just ran out of steam. But the idea kept coming back to me, and then, finally, last year I started it up again, but from a different angle, with the benefit of years of development in my mind, and now it’s coming along really nicely. It feels like something I’m going to pursue to the end because it’s something I’m thinking about and getting excited about and making natural connections and making deeper the more that time goes on. To me, that’s the sign of a good idea: It’s one that only gets more exciting the more that you think about it, rather than the inverse, an idea that you’re really excited about out the gate, and then by not just week 2 or 3, but month 2 or 3, year 2 or 3, you’re fucking exhausted of the thing, you don’t want to do it anymore. To me, that signals that idea is not worth it.

“I don’t subscribe to the philosophy that writing is a torture. I think if you’re not enjoying the writing process, you’re in the wrong career.”

Similarly, this is why I pursued fiction over nonfiction: I dreaded the idea of writing a nonfiction proposal, selling the book, being given a deadline, and then halfway through the writing, realizing that I didn’t want to do it anymore, or the idea had become irrelevant, or my thoughts had changed. That’s another part of the process: You need the courage to start over or walk away if the idea isn’t right, to not push it and not force it. Not to say you should run away from a challenge, but it should be fun on some level. I don’t subscribe to the philosophy that writing is a torture. I think if you’re not enjoying the writing process, you’re in the wrong career. You can hang everything else that comes with it—you can hate the marketing, you can hate the elevator pitch, you can hate the hobnobbing and ass kissing, you can even hate some of the revising on days when you’re really feeling down—but if you hate the simple act, then become a plumber or something. Not to be a dickhead about it, but there are too many writers in the world to indulge in your non-singular angst over something that is just part of it.

Is there a world in which, if given the opportunity, you would like to just write novels and/or book-length things full time, without having to balance it between myriad other things, including a full-time media job?

My truest awareness is that it’s very hard to write books for a living. I can honestly think of nobody who does, even the most successful writers. The economics of it are so brutal. Even people who I regard as wildly successful are teaching, or they’re doing something else, or they have a day job. Romantically speaking, I would love the freedom to not work and just write whatever I want whenever I want to write it. Unfortunately, I do have to pay rent and pay for my groceries. I have the parental safety net of my mother’s love, but I do not have millions of dollars in a trust fund sitting for me, and neither does my wife. I’ve made my peace with the idea that it’s going to be something I pursue on mornings and nights and weekends for the longest time, maybe forever. If I’m lucky, I would be able to take some time off here and there, go to a residency or take little staycations, but that’s as much as I can think of. I’m truly hard-pressed to think of anyone who can sustain themselves purely off of books. It often involves compromising in some form, whether that means doing a podcast or having some advice column or whatever it is. There’s always some other thing that has to be happening. I wish that weren’t the case.

The alternate reality is people who are totally self-publishing and they’re putting out dozens of books a year, which, with respect to it, is just different. My ideal vision of writing is that I’m writing when I want to, because I want to. That’s another component of having the courage to just not write if it’s not coming to you, if you don’t have the idea yet. You need to have that middle ground of pushing it but not forcing it, while also not just waiting infinitely for inspiration to strike.

At a certain point, you just gotta do it.

Nike was right. Whatever option you pick, it’s legitimate, whether it’s writing or not writing, but it’s a choice.

To facetiously circle back to the main question: Should I write a book?

It depends. If there’s no obvious natural extension of “what people want from you,” then you have the luxury of trying to figure it out for yourself. I will say, when you land on the right idea, it’s very exciting, and you will learn other things about yourself and your practice. One thing that I was not expecting when writing this book: I was worried about my nonfiction creeping into my fiction, but now I’ve realized that the opposite thing has happened, but in a positive way. My fiction has crept into my nonfiction in ways that I could not have predicted, in ways that I can’t even necessarily articulate out loud, but I just know it is true, and that’s been really nice. The best argument I can make for writing a book is that the simple act of writing it—not even publishing it or touring it or whatever—will take you from one place to another. You will learn things about your practice that you did not know before you undertook it. Working in what is essentially a dying medium, carried along by romantics and sociopaths, the best reason to do it is because you want to do it.

“The best argument I can make for writing a book is that the simple act of writing it … will take you from one place to another.”

If anyone wants to become rich and famous as a writer, they should just go to law school instead. There are so many better ways to make money and a name for yourself, that I’m shocked about why anyone would be a writer, aside from the fact that it rules, but it’s not going to make you a trillionaire. The world certainly doesn’t need more novels, so if you write one, you should do it because you really want to do it. There’s no purely intellectual reasoning of why someone should do it versus why the world needs my thoughts and not other people’s thoughts. You kind of do need the semi-delusional belief of, I want to do this because I like my shit and I like what I got going on, and I think other people could fuck with it, god willing, so let’s see what happens.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

P.S. Today’s thumbnail photo is of Bell Works in Holmdel, New Jersey, a.k.a. the Severance building, where I attended some promo event thing a couple weeks ago. That’s what being a Writers Guild member is all about.

Etc.

Absolutely no one asked me to do this, but I have been writing an unexpected amount recently for [REDACTED], including about Severance, Hayao Miyazaki and Ghibli A.I. slop, and the emerging genre of former magazine titans reminiscing about how great the old days used to be now that things are not.

I also went on a podcast to talk about last month’s 9-to-5 pretenders post, which went bigger than I thought it would, both to my pleasure and to my embarrassment because I forgot to include a necessary paragraph lol

I haven’t been doing a ton of reading otherwise because, to be perfectly frank, I have been in the throes of depression due to all the usual suspects and more. My glibness belies how awful things have felt, partly because I cannot stand being a fucking buzzkill here, the one and only personal–public outlet that feels truly mine. Haha. Maybe another time!

If you are reading, watching, or consuming (in whatever form) good things that you would recommend, please do so.

This newsletter is unedited except by me. If you spot any typos or errors, please notify me, to my mortification.

That said, please do not call me a sellout if I do other things.

Excellent interview, Jenny. I want to read Jeremy's novel now. And I want to read yours!

I reviewed the Graydon Carter memoirs on my Substack this month. While I thought it was entertaining enough, it's amazing how little he's considered his actions in life beyond making money, meeting celebrities, and opening restaurants. That's how someone ends up with an all-white editorial staff at Spy, The New York Observer, Vanity Fair, and Air Mail!

hi! can relate to everything written, especially the idea of writing some essay and being like could that be a book and then realizing oh no it is definitely not a book. and the pleasures of fiction are the best pleasures! why wouldn't that be the dream? heck there are even wild bestsellers that I definitely was like no, why are you a book, so much of it is about minutia that I didn't care about because the writer was just a normie and the part that was originally a New Yorker article is the only good part!