The truth about writer's block

It shouldn't be controversial to say that some things actually do take work and discipline.

By the time I was 13, I had written something like three novels.

They were more like novellas, if I’m being completely honest, or narratives resembling those old-timey cartoon fish corpses that you don’t see so much anymore: head and tail fully intact, with everything in between—the boring “journey” part of my hero’s journey, also known as the bulk of the plot—left stripped to the bone. These manuscripts were in no way publishable, as I learned when I mailed a printed-out copy to one of the Big Five publishing houses in New York. (No response, big surprise.) But my failure to make it out of the slush pile didn’t bother me at that tender age; back then, I wrote for the sheer pleasure of it, scribbling down character traits and bits of dialogue in a notebook whenever I had a spare moment during a dull class. My appetite for making up stories was so voracious, it was as if I had the Muses themselves whispering half-baked YA fantasy ideas directly into my ear all day.

Then, one day, their murmurs stopped, and I didn’t write creatively again for the next six years.

This was just writer’s block, I told myself the first time I found I could no longer write. I got into the habit of repeating this every time I stared at a blank page in my notebook or the blinking cursor in a Word doc: Writer’s block was the reason why the stories wouldn’t come anymore, but that was fine, there was no point in forcing it, the Muses would talk to me again when they felt like it, and then the words would flow once more.

It was the worst possible lesson I could have internalized, and one that I’m still trying to unlearn.

Writer’s block and its assumed antidote, divine inspiration, are tenets of one of two popular conceptions of writing: that of writing as the organic fruit of tortured, artistic savants. This is in opposition to the other conception: that of writing as the endlessly replicable and virtually worthless end product of anyone—temps, chimps, bots—arranging letters into sentences. There may be some shards of truth to both opinions, but the trouble is when the two poles are planted firmly in the ground, becoming immovable stakes on which entire foundations of belief, ethic, and valuation are built. In the second view, writing is devalued; how lucky we are that the rise of ChatGPT and A.I. slop—and, even before that, digital forms of text not given physical purchase by paper and ink and printing presses—has convinced many of the stupidest people alive that that is the whole truth. The first view, meanwhile, overvalues and oversells writing as a gift bestowed upon particular individuals both beloved and tormented by the gods. This “chosen one” affect has long been part of the self-important mythology of writers, but it gains a particularly noble, resistance-y sheen nowadays, beneath the cold glare of all that threatens writing and art and creative and intellectual fulfillment in these troubling times: you know, fascism, capitalism, technology, and so on.

But could there be a third conception of writing beyond these two positions? How about this: Writing is work and labor and discipline, and, as with other skills, if you want to be good at it, that requires work and labor and discipline.

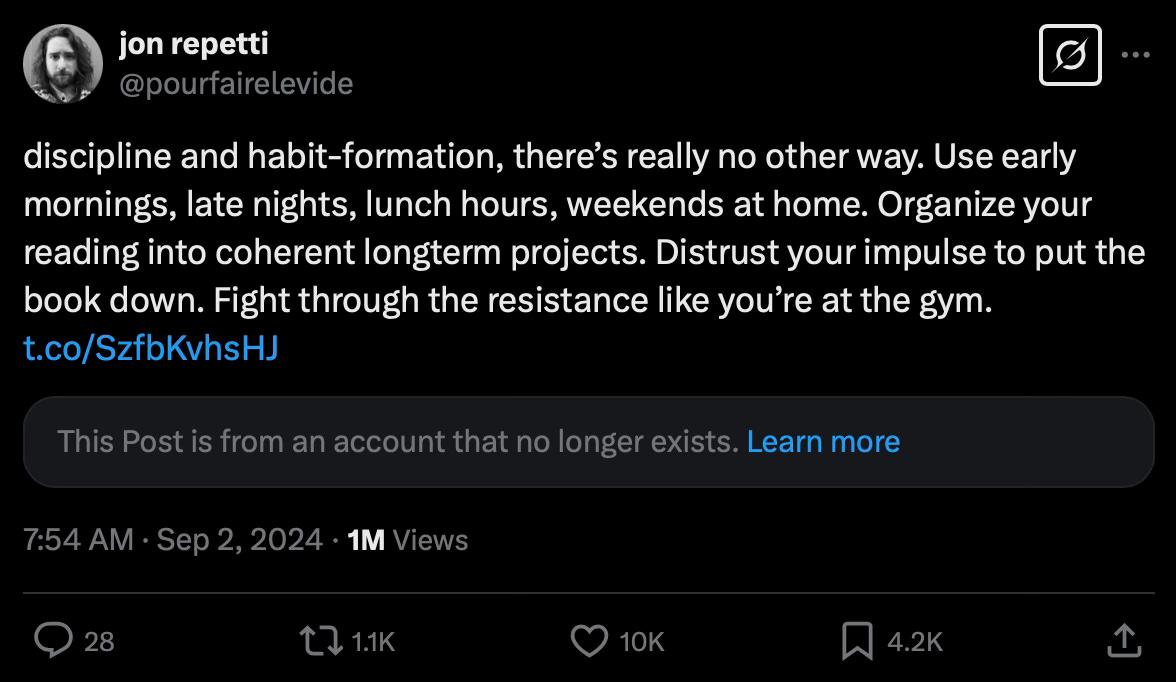

This may strike you as obvious, even obnoxiously so, but I don’t think it’s a stretch to posit that many people think otherwise, especially in the shadow of the aforementioned threats of, you know, fascism, capitalism, technology, and so on. I have noticed some measure of hostility to the notion that craft or intellectual or creative work demands some measure of effort, at least if you’re going to be serious about it. One such illustration of this sentiment that I jotted down back when I started toying with this essay last September (I’ve had a lot going on, okay?) was a now-deleted tweet that snarked, “i think you can actually have a beautiful intellectual and artistic life without allowing assembly line capitalist thinking to structure every aspect of your life” in response to writer/PhD Twitter guy Jon Repetti declaring that the only way to be able to sustain such endeavors outside the tiring demands of work was through “discipline and habit formation,” a.k.a. “early mornings, late nights, lunch hours, weekends at home.”

The skeptical tweet, alongside several other such responses from those who rolled their eyes at Repetti for, I guess, grad student-ing too hard, are typical of an increasingly popular pushback against the strictures placed upon us by the overwhelming force commonly referred to as “late capitalism.” Under this system, the relentless pursuit of scale and exponential growth has devastated the planet; the “grindset” espoused by entrepreneurs and hacks (many one and the same) has led to the fetishization of wealth and productivity above social and moral good; large swaths of the population have become lonelier and unhealthier and sadder while lining the pockets of the fat cats’ at the top of the pyramid, and it’s not just because those workers are all massive losers. Of course people are wary of attempts to coax them into more work, into—to borrow the language of the deleted tweet—“assembly line capitalist thinking” outside the parts of their lives that have already been ceded to the enemy.

But this line of thinking, when taken to its pop-politics self-soothing natural conclusion, falls into a trap: It conflates one possible answer to the problem—that is, finding a way to carve out a small possibility for self-enrichment and creative fulfillment even under the less-than-pleasant circumstances of “late capitalism”—with the problem itself.

These days, a bastardized dogma of “self-care” is often presented as the balm to those exhausting conditions: It’s okay, I know life is hard, how about a bubble bath, a two-hour TikTok scroll, a Netflix marathon, too much DoorDash, a cartful of more stuff you don’t need, eternal fleece-lined hibernation? These are all completely normal and fine things for someone to indulge in, obviously. But when familiarity, ease, and comfort (“comfiness,” pardon me) become the default state, such that a suggestion that a meaningful-to-you project or undertaking will take discipline and work to achieve, then the mass-market form of self-care starts to look a little more like merely giving yourself permission to lie down

If you want to lie down, go ahead. I take no issue with that; I am in fact typing this from a horizontal position in bed, where I, too, enjoy partaking in the popular pastime of “rotting.” But be honest with yourself: Do you want that thing—a dream, a goal, a commitment—as much as you say you do? So many of the conditions and the solaces of contemporary life, whether that’s burnout or the stultifying surface-level remedies meant to treat it, are designed to keep you exhausted, to kill any intellectual curiosity, to pacify and placate. It’s too easy to fall placidly into those rhythms, just as it’s too easy to fool others and yourself into believing that if something is meant to be, it will be. But this elides what it actually takes—and costs—to make it happen.

In spite of my embarrassingly public confession to aspiring to “talent,” for instance, the reality is that I’m not owed a book deal or an enviable assignment or a plum star gig, regardless of my personal feelings or the yoke of capitalism or whatever. Under these constraints, what can I do? For starters, realistically speaking, be clear-eyed about my priorities and what they will cost me. Whether it’s writing, learning a language, or I don’t know, becoming a Marxism scholar in your free time, it’s going to take some level of sacrifice, rigor, discipline, dedication, and work at the expense of something else, however big or small.

Which brings me back to writer’s block. After the six or so years that I couldn’t write anything, what made me finally start again was a creative writing class in college. I had to write or I would get a poor grade, which, it turns out, is just as good of a motivator as the Muses planting loglines in my head. I wrote poems and short stories for that class; later, I wrote blog posts for a part-time job; eventually, much later, I wrote articles for a regular paycheck. The more I did it, the more I could do it. (In that way, writing is, as the writer Rayne Fisher-Quann proposed in a recent essay, “a lot like walking,” although I guess I’m now approaching it a little more like committing to a minimum number of steps each day.)

And when my words petered out once more—did that bout of writer’s block come first, or did my stopping?—I knew what I had to do, although it took me another few years to do it. (Like I said, I’ve had a lot going on!) But this is the truth: The way through writer’s block is not to wait around for some empyrean bolt of lightning to strike you—it is simply to write. So here I am, up late after another long day making an honest living. I can hear the words; all I have to do is write them down.

— Jenny

P.S. Today’s thumbnail photo is one I took of Shanghai in the early morning. Talk about rise and grind…

Etc.

A couple other links I was going to try to work into this essay, but couldn’t find the room for:

Max Read on the secret of blogging: “The single most important thing you can do is post regularly and never stop.”

Defector’s Alex Sujong Laughlin on quality versus quantity: “The lesson here is that trying too hard to make something perfect—or in the context of online media, something “sticky”—will ultimately harm your final output. The more certain route to creating something good, whatever “good” means to you, is to create a lot.”

I already linked Rayne Fisher-Quann’s essay about writing, but I want to highlight one more line that I liked: “[A.I. tool] attempts to separate the mythology of writing from the work of writing, as though the quotidian labour of expression is something that keeps you from your ideas rather than the exact process by which you discover them.”

On another note, speaking of good writing, one piece I edited last year that I think is some of the best writing on (and off) the internet is Franklin Schneider’s essay about telemarketing that’s really actually about the dark soul of the market and America and all its hucksters. The piece is months old by now, blah blah blah, whatever! I will never stop recommending it!

I found myself moved by Timothée Chalamet’s SAG Award speech, and not just because I unironically stan Timmy (I do), but also because I can’t help but like artists—actors, writers, musicians, whatever!—who aspire to greatness and aren’t afraid to let that naked, unflattering desire show. (See also: Jeremy Strong.) Sense a theme???

I’m in the club crying over the upside-down flag at Yosemite’s Firefall.

This newsletter is unedited except by me. If you spot any typos or errors, please notify me, to my mortification.

I hate it when people write off hard work as an act of allegiance to capitalism – it's so lazy! Which makes me sound like some sort of hard work addict à la Kim Kardashian in that video where she's telling young people their problem is they don't want to work. But it's more like what you said, where it's just a part of liking something enough that you're willing to put up with some discomfort. And also, how on Earth does anyone expect to 'overthrow capitalism' or whatever by not putting work into it? Even if it's for a boss and not your own creative pursuit, I think having pride in whatever you do, however soulless, sets the foundation for creative energy. Loved this piece.

Loved reading this. I've been thinking a lot about Jon Repetti's tweets and the (imo extremely weird!!!) backlash he got for them—I think he perfectly described what it takes to sustain an intellectual/creative life.

The rewards are worth it: you get to engage more deeply with the world, with other people's ideas and perspectives and insights, and you get to make work that you're proud of…and work that can shape other people's intellectual/creative lives, too!

Basically nothing good happens without time and devotion. The idea that writing can just happen, that intellectual curiosity can be fulfilled without any real effort—it honestly feels more misleading and dispiriting to me!