For the past month, I’ve been watching a man called Hubs gradually lose his mind.

Hubs is not his name, probably; I don’t know what is. Hubs is what he goes by on TikTok, where, as one of scores of “day in my life” influencers, he posts tightly edited videos of himself hitting the gym, making protein shakes, staring at his computer, playing with his kid, and, until recently, working a 9-to-5 job at an office.

You may have seen Hubs—or videos like his—before on one social-media feed or another, even if you’re not one of the millions(?) of sickos like me who partake in the ritual of cognitive cleansing via watching internet strangers perform mundane tasks. Often, when such videos escape containment—from TikTok to, say, the open-season mayhem of Twitter—they are roundly mocked, held up as textbook illustrations of the monotonous, depressing rhythms of office jobs, unvarying routines, and contemporary life itself. Occasionally, a video may break from the standard cubicle course—a weekend in Chicago, perhaps one filled with a few drinks and actually pretty dope museums and yet another marg tower—although these, too, are susceptible to mockery, whether for their perceived “inauthenticity,” “privilege,” or fundamental “basic”-ness.

The 9-to-5 DIML, as a genre, is dull by design. While some viewers may watch with a sense of aspiration and envy—perhaps one day they, too, can land a desk job with a salary, benefits, and most importantly, the white-collar leisure to be able to film their own DIML TikToks—mostly these videos invite a comfortable, lethargic recognition. Fellow 9-to-5ers recognize themselves in the tedium, and draw comfort from the audiovisual affirmation that others, too, are working perfectly humdrum jobs, living completely ordinary lives, and that’s not only okay, but worthy of esteem. The growing aesthetic and spiritual appreciation for the quotidian 9-to-5 is an answer to widespread job insecurity and dissatisfaction, the erosion of the fantasy that is the American Dream, and all those years of “do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life” propaganda, a siren song that has surely resulted in heaps of dashed dreams and too many creative-arts majors to count.

But the tacit agreement between 9-to-5 DIML content creator and fan—you and me, bud, we’re all just regular guys grinding our way to the weekend—is precarious. Its biggest threat is, ironically, how well the creator has embodied and sold that message. The more believable and relatable they appear, the more views their videos will attract; the more views their videos attract, the more followers they gain; until, eventually, they have gained enough followers to be able to quit the 9-to-5 that they made the basis of their persona, in order to pursue the new American Dream: becoming a full-time influencer.

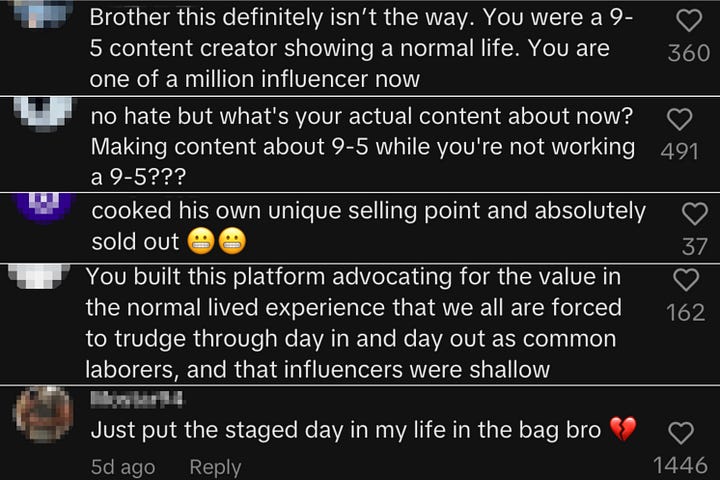

That’s what Hubs did; it did not go over well. Since he quit his job as a senior benefits analyst at a Fortune 500 company, the comments section under his videos have been littered with sentiments like “Nah we’re here to watch you struggle with us cmon” and “Your success was based on being relatable to us normal 9-5 people. With your content, it felt decent to do normal work. The fact that now even you are leaving 9-5 shows us we are worth nothing.” Hubs renting a WeWork desk and calling it his “new 9-5,” as if to cloak his life upgrade in the worn slacks and button-downs of his humble beginnings, only inflamed many fans’ ire:

And the succinct:

Meanwhile, elsewhere on—where else—TikTok, catastrophe was unfolding in the “NYC influencer”-sphere after some chick called said influencers boring, kicking off a whole cycle of debate and offense and passive-aggressive comments and backlash that is legitimately too boring for me to summarize. (And that’s saying a lot.) What caught my attention, though, was the resentment of the viewers who were witnessing the influencers’ meltdowns. The deepest resentment wasn’t aimed so much at the general out-of-touch-ness of (largely) wealthy young white women in Manhattan, but at the appearance that those women were almost cosplaying as 9-to-5ers, getting up early for 5 a.m. pilates classes (a time otherwise occupied by people who actually had to squeeze in a session before clocking in to work in the morning) and writing their to-do lists (typically consisting of “film video,” “edit video,” and maybe “nail appointment”).

It’s the same seam of resentment that has been widening against the cooking influencer Wishbone Kitchen, who made her name posting videos of herself working long, grueling hours as a private chef in the Hamptons, and whose post-success content now heavily features her dreamy Hamptons house, luxury PR hauls, and five-star hotels in Paris. “She’s veeeerrrry close to losing that spark that made everyone like her and going off the insufferable deep end that comes with influencer fame,” one observer posted on a snark subreddit, a place that I should stop looking at if I want to get into heaven.

What these three cases illustrate is the real paradox of many influencers, especially the ones who originally built their brands as “normal” people. What differentiates our modern-day online celebrities from the real celebrities of yore is the veneer of relatability, all the better to cultivate parasocial relationships with their followers. They get familiar, they overshare, they reveal vulnerability in front of the camera, and fans delude themselves into believing they really get each other on a personal level. (Even the TikTok-famous heiresses who show off their Van Cleef and Birkins to pass the time have to possess some quirk of personality, some confession of insecurity, to truly win followers’ hearts and minds.)

This relationship can tolerate some degree of glow-up and money and opportunity on the side of the previously “normal” content creator. But there’s a fall-off cliff, past which a creator no longer appears relatable to the viewers whose collective eyeballs contributed to their success. It’s even worse when they have the gall to act as if nothing has changed, like they remain the same striver they were in the beginning. That is the real betrayal felt by the former fans of creators like Hubs: The 9-to-5 pretenders don’t even have the dignity to give up the pretense that they haven’t made their great escape from the mud that all the rest of the schmucks are still stuck in. That, in turn, makes “us” feel bad about ourselves, the greatest sin that any content creator can commit.

To pursue the new dream or to stay chained to the cubicle—who among us wouldn’t make the same choice, if given the option? For the creator, it’s a lose-lose situation, or at least a very slippery tightrope to walk. Still, I suspect the savviest of these DIML influencers might just be the ones who know not to aim too high: They’ll never be accused of stealing 9-to-5 valor, because they never leave their 9-to-5. They do their little office jobs, they earn enough side income from TikTok to buy a house furnished in cream and beige, and they become someone for the average viewer to aspire to rather than to begrudge. They are the version of you if you would just get your life together, try a little harder, put yourself out there more, you tell yourself. Life may be a grind—but they’re right there next to you in the trenches, as real as they come. Now check out their Amazon storefront to get exactly what you need to be just like them.

— Jenny

P.S. Today’s thumbnail photo is of New York City’s Financial District on a foggy evening after my own 9-to-5 in 2018. Different times…

Etc.

I am basically ambivalent about Anora, but I did enjoy this hetero-pessimist analysis of the film by Rayne Fisher-Quann.

For Slate, Scaachi Koul followed the stories of three liberal women who wanted to leave their right-leaning husbands. What happened next probably won’t shock you.

I tried making the “high protein bagels” that have been around for a while among yogurt/cottage-cheese heads and frequently blows up again on TikTok. They’re good!

But also, crucially, I have discovered my joy for Japanese vegetable curry paired with tofu, which I previously shared in my Regular Food Reviews for Gawker. I used to serve it on short-grain rice; currently, I’m eating it with a couscous-quinoa “harvest blend” type of thing, as well as roasted cabbage. Fucking great!

(Relatedly, I am thinking of reviving Regular Food Reviews in some form. If that interests you as much as it interests me, please let me know.)

This newsletter is unedited except by me. If you spot any typos or errors, please notify me, to my mortification.

Feels like this piece misses the grander point - our alienation and isolation is crystallizing so intensely as anxious normalcy that we have now commodified relatability. What the fuck happened to getting a drink with your coworker and complaining about your job? Depressing as hell

Everything is computer and everything is performance. Good piece!